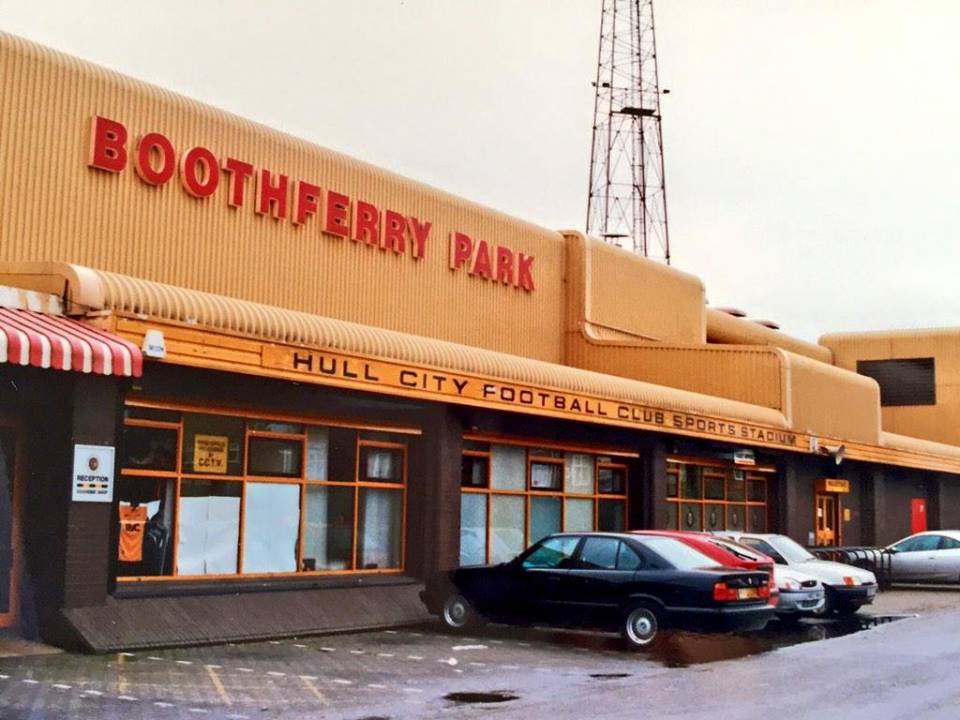

For some people, Hull City didn’t exist until the club joined the Premier League and entered the national consciousness. For long time City fans though, the Tigers are far more than a single match or season, they are the sum of childhood memories of standing on Boothferry Park’s ‘well’, of recollections of Simon Gray coach trips to away games, even of events not witnessed first hand but passed down from a previous generation of Tiger Nationals. Hull City is a rich tapestry comprised of many individual and overlapping threads.

Some threads are more important than others though, and we set out to define what it is that makes Hull City unique, different from every other club in the land. What are the key events, people, sights and sounds that combine to form the soul of Hull City? Not every entry has to be of monumental historic importance, but it has to be quintessentially Hull City…

Entries by Ian Thompson, Richard Gardham, Mike Scott, Les Motherby, Andy Dalton and Matthew Rudd

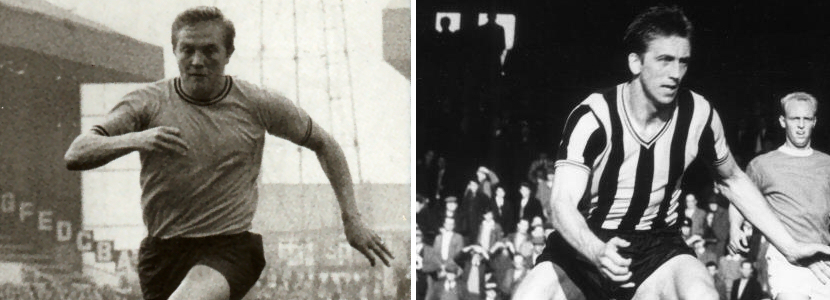

WAGGY AND CHILLO Dramatis personae

The greatest strike partnership in Hull City’s history, in spirit and backed up easily by the figures. Upon the arrival of cocky and stocky Ken Wagstaff to partner Sproatley’s own centre forward par excellence Chris Chilton in late 1964, the pair never looked back. The giant Chilton’s brand of brave, strong, uncompromising marksmanship yielded the individual club record for goals which nobody will beat; Wagstaff was the artier, more cultured footballer, devilish at getting into the right positions and fearless when faced with any chance, in any game, against any goalkeeper.

The pair of them make sure in their dotage today that supporting forwards Ken Houghton, Ian Butler and Ray Henderson get their share of the credit as suppliers and supporting characters, but for seven years the name of Hull City was better known than the club’s league status may have deserved because of these two men at the helm, masters of the simple-but-difficult goalscoring craft. They scored 366 League goals for City on aggregate in 15 years of involvement; 252 of which came as a partnership between Wagstaff’s debut in November 1964 (in which both he and Chilton scored) and Chilton’s departure for Coventry in August 1971.

A staggering 52 of these were hammered in during the Third Division title winning season of 1966, in which Houghton, Butler and Henderson also each reached double figures. Wagstaff also scored a comparatively whopping four goals in FA Cup quarter finals, a round of the competition which remained alien to Hull City thereafter until 2009. Maybe all these stats really should have appeared at the start of this paragraph, as they say more than meagre words.

HALF TIME v LIVERPOOL, 1989 Heights of Joy

Rarely do lower league football clubs have moments of genuine global significance. Premier League clubs on the other hand, do so routinely, so City beating Liverpool in successive Premier League seasons can make it easy to lose sight of what a remarkable achievement it can be for a small club to best a genuine world class footballing side, no matter how briefly.

In 1989 the Tigers, an established second tier side thanks to the calm administrations of manager Brian Horton but now piloted by dour Leeds-type Eddie Gray, reached the Fifth Round of the FA Cup after solid wins at Cardiff and Bradford and drew a plum tie at home to Liverpool, a global phenomenon in the 1980s.

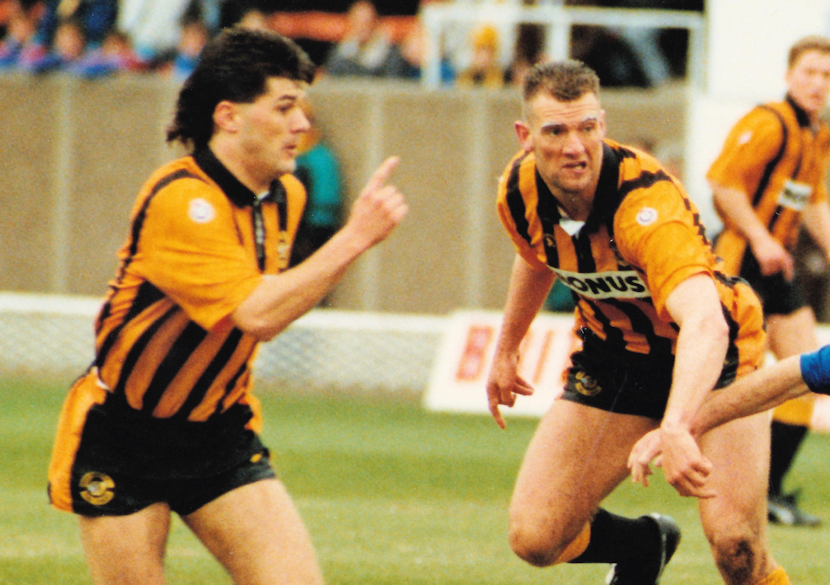

The masses crammed into Boothferry Park (the attendance of 20,058 that day wasn’t subsequently bettered in the old place) and watched in amazement as goals from bludgeoner Billy Whitehurst and arch-poacher Keith Edwards saw City return to the dressing room at half time with an unlikely 2-1 lead. Boothferry Park witnessed a remarkable spectacle at half time, an almost deafening hum of people talking in low tones to each other about how unbelievable this all was. It was a sound that many football fans will never experience.

Alas, it all faded away as quickly as it arose. Liverpool soon assumed a second half lead and the plucky Tigers went down 2-3. City narrowly avoided relegation while Liverpool suffered their worst of tragedies two months later when the South Yorkshire Police force facilitated the death of 96 supporters in the sheep pens of Hillsborough.

But just for a moment, whispering scarcely credible predictions over steaming cups of half-time Bovril, the little guys from Hull believed they were going to rock the footballing world. Nice feeling, that.

IAN McKECHNIE FETED WITH FRUIT Fan Culture

Jovial Scottish custodian Ian McKechnie was a mainstay between the sticks for City over eight seasons in the 60s and 70s, but despite all his agility and bravery – team-mates said he was brave almost beyond the call of duty – it’s the pre-match routine between him and City fans which was dominant in securing his place in City folklore.

Numerous stories have been related, but McKechnie’s own version has to be taken as the definitive: one Thursday afternoon after he’d left Boothferry Park following treatment, he walked along North Road and then Anlaby Road and noticed a Jaffa orange in a shop – a wet fish shop, oddly – and decided to buy it to scoff during his walk.

Two young lads then shouted their good wishes for the coming away game to him, and McKechnie, still chomping on his snack, responded with thanks. Two weeks later, at the next home game, two oranges landed on the pitch near McKechnie’s goal, almost certainly from the same two lads.

McKechnie, who happily sucked on the oranges during the game, related afterwards to the Hull Daily Mail whom he believed had thrown them and why, and subsequently numerous oranges started appearing in his goalmouth as a ritual at each game. Some got squashed or bruised, but he’d end up taking half a dozen or so home each time.

One week, an orange had a phone number and ‘I LOVE YOU’ on it which McKechnie showed to the Mail reporter who then arranged a meet up. Although McKechnie was greeted by an attractive woman upon ringing the doorbell, it was her five year old daughter who had chucked the fruit.

Another time, a fan was arrested at Sheffield United for hurling an orange McKechnie-wards, and the keeper himself appeared in court on the supporter’s behalf later to explain away the reasoning.

Given that McKechnie, who played for City between 1966 and 1974, was also responsible for English competitive football’s first penalty save in a shootout (in the Watney Cup semi against Manchester United in 1970; he also missed a penalty, a further first), he could have got uppity about being more associated with fruit than football when his City career ended. But he was truly proud of his unique contribution to player-fan interaction at a time when fan-fan interactions were rather more feisty.

McKechnie died in 2015 and, at the funeral, his family threw oranges into his grave. It’s impossible to define how fitting as a final gesture this was.

MIKE SMITH Dramatis Personae

It was seen as something of a coup for City when Wales manager Mike Smith was appointed as the club’s new boss as the 1980s got underway, though it was tempered by the knowledge that he had never played with, nor managed daily, any professional footballers. An amateur player by choice and ex-teacher, he had overseen the Welsh into the quasi-quarter finals of the European Championships of 1976 and within a game and a dodgy penalty at Anfield of the World Cup two years later, but taking on City was new territory for everyone involved.

Smith was more teacher than coach, more athlete than footballer. Tales of his training programmes remain legendary, with the squad barely touching a football due to Smith’s insistence that they ran and ran and ran all the time – round the pitch, through Boothferry Estate, in the gym. His Friday night sessions became notorious as they rendered the players knackered before important games while also struggling to understand what he required of them when a ball was at their feet.

Nevertheless, the fitness of the players did improve and the remainder of 1979/80 saw a run of form that allowed City to avoid a first ever relegation to the Fourth Division, courtesy of a win over Southend on the same day that two other Hull teams were eggballing around Wembley. Smith’s long knives came out over the spring and close season, however, with a stack of seasoned and established professionals released or sold – his decisions to let Roger deVries and Stuart Croft leave especially saddened the fans – while those that survived were evidently hacked off and his signings distinctly out of sorts.

There was an exception, a glorious one, in the shape of goalkeeper Tony Norman, who pretty much single-handedly rescues Smith’s legacy by being unbeatable and unmatchable for eight terrific years with the club after joining from Burnley. He also took credit for getting youngsters from a gifted youth side into the first team picture, with Brian Marwood, Steve McClaren, Gary Swann and Garreth Roberts all becoming regulars, the latter even becoming skipper at the age of 21.

He also wasn’t afraid to give 16 year old striker Andy Flounders regular football. He needed to do something with the strikers, after all. Keith Edwards was scoring regularly but hated the new regime, chucking his shirt at Smith after being substituted during a goalless game against Brentford at a time when City were so woeful and so short of ideas that the demotion to the bottom division they had been so relieved to avoid the year before was now inevitable. Smith signed two non-league forwards in Billy Whitehurst and Les Mutrie, both of whom had to be an improvement on the plodding Welsh international Nick Deacy, brought in by Smith early on after a nonentity career in Holland.

City went down with games and weeks to spare, and Edwards was sold early the next season. Whitehurst became a regular up front but couldn’t score (or head, trap, run…), but Mutrie, at 29 one of the oldest Football League debutants of all time, settled in well and scored quite freely alongside him. Smith’s side were just a middling, inconsistent, uninteresting team when the club was thrown into the national spotlight suddenly in February 1982 thanks to Christopher Needler revealing he had been advised to stop putting funds in.

Receivership documents were drawn up and Smith, along with one of his assistants, was sacked to save cash. Most of his players remained – though Deacy was one quick to jump ship – and when Don Robinson and Colin Appleton came in, they made a team that could score, win, defend and get promoted from the squad Smith left behind. The youngsters from the ranks became legends, as did Whitehurst, Mutrie and the immense Norman.

Smith managed Egypt for a bit, winning the African Cup of Nations, and had a second spell with Wales in the 90s, but City is the only club he ever managed. It was a strange time, unique in terms of the way the team was plummeting and the financial struggles that would somehow salvage him from a worse ultimate fate, yet despite the bigger picture surrounding the club, and the handful of decent, if misused or mistreated, players he left behind, there isn’t a great deal of lingering affection for a manager whom, at the time, the fans didn’t get chance to really dislike.

THE GREAT ESCAPE Talking Points

Between mid-1986 and 2004, Hull City fans endured little but relegation, winding-up orders, the sale of the club’s best players, and chairmen and boards that ranged from the inept to the corrupt. They had seen both a once-great stadium crumble to ruins and Simon Trevitt playing at right-back.

That isn’t to say that the club’s dark ages were without their good points, however. And chief among them stands the ‘Great Escape’ of 1999. Given the circumstances, to a generation of City fans who had known nothing but pain and despair, our survival that season felt like a promotion.

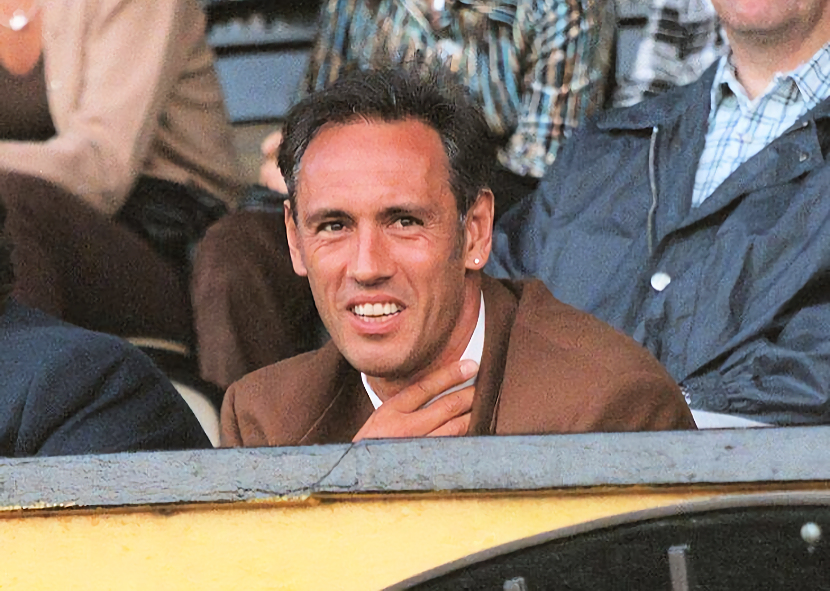

1998 had been as grim a year as Hull City had ever experienced. David Lloyd’s Plan A seemed to be to lead us to extinction off the pitch. His Plan B was to allow Mark Hateley to lead us to the Conference on it. By November we were bottom of the bottom division, six points (briefly nine) off the rest. Thankfully, Lloyd ran out of toys to throw out of his pram, and sold the club to a consortium backed by local farmer and former Scunthorpe chairman Tom Belton. Belton’s first task was to fire the awful Hateley. Midfielder Warren Joyce was temporarily given the reins, and brought in former Bolton team-mate John McGovern to assist, as he had no plans for retire from playing just yet.

Joyce’s impact in the league wasn’t immediate. A memorable 1-0 win at home to Carlisle thanks to a last-minute Craig Dudley goal gave the fans some hope of survival, but this was followed by four dispiriting defeats to Torquay, Swansea, Chester and Shrewsbury. Indeed it was a morale-boosting FA Cup run that seemed to instil belief in the players. High-flying Division Three side Luton were dispatched in the second round, leading to a visit to top-of-the-Premiership Aston Villa in the third. In the 3-0 defeat at Villa Park, City – still 92nd in the league – did not disgrace themselves.

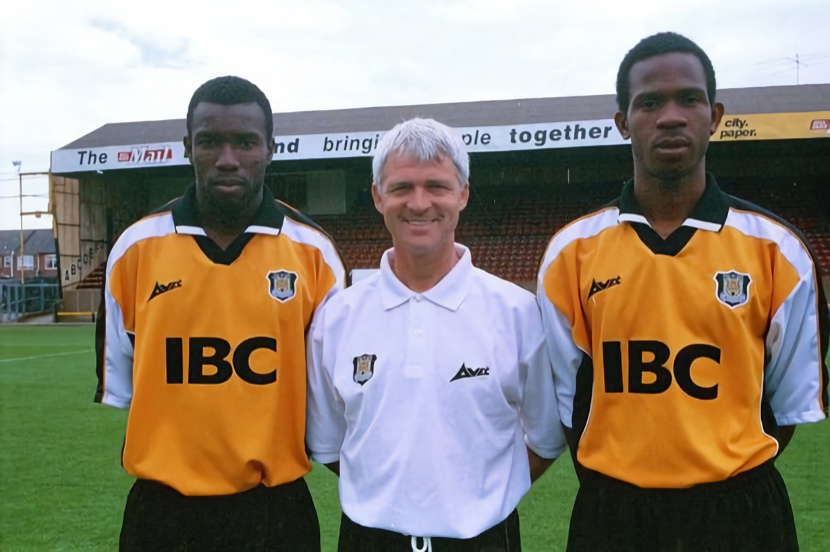

However, it was relegation that needed avoiding, and Joyce set about building a team capable of such a task. Out went Hateley’s powder-puff nonsense of French, Hawes, Hocking, Rioch and Whitworth. In came the heavy-duty Whittle, Alcide, Perry, Whitney, Swales, Williams and Oakes. Mark Greaves was given a first-team berth. Oh, and before we played in-form Rotherham in early January, a double signing was made: Mark Bonner came in on loan and was to score the only goal of the only game he was to play for us, and former bouncer Gary Brabin was introduced to the City faithful. Within 10 minutes of his debut he’d slide tackled a Rotherham player with his head.

The 1-0 win at home to Rotherham was followed by a 4-0 win against fellow strugglers Hartlepool, in which Brian McGinty’s brace was to be his last telling contribution to the City cause, unable as he was to oust the excellent and underappreciated Gareth Williams from left-midfield (go on, admit it, you can’t even picture him, can you? For shame…). This was the first time City had won back-to-back league fixtures in more than two years. This was followed by two 1-1 draws, away to Peterborough, in which Jon Whitney scored from what seemed like 60 yards, and at home to Shrewsbury, in which Brian Gayle scored what seemed like the 200th own-goal of his career.

Then came Brentford away. Brentford hadn’t lost at home all season. They were top of the league (and would go on to win it). The near 2,000 City fans that packed into Griffin Park’s marvellous old away end made more noise than I can ever remember us making as Colin Alcide scored on his debut and David Brown scored a second-half volley to give us a memorable 2-0 win in what was surely City’s game of the 90s. As Scarborough lost 5-1 to Exeter, we came off the bottom of the league for the first time since August.

A 3-0 defeat at Rochdale in our first-ever televised league match set us back, but with Brabin and Whittle at the heart of the team we were never going to stay down for long. Indeed it was the former who was to score our winner at Darlington in our next game, and the latter who was to score against Barnet in a 1-1 draw the game after that. A 1-0 win at Halifax the following week kept us off the dreaded relegation spot, as Scarborough, Hartlepool and Torquay all flirted with the bottom position, while Carlisle – once in the play-off positions – entered freefall.

A lull was to follow in the shape of a goalless draw at home to Mansfield followed by a 2-0 defeat at high-flying Cambridge. Again though, City’s new-found powers of recovery came to the fore as Leyton Orient – in the play-off positions – were beaten 2-1 at Brisbane Road. A Gary Brabin overhead kick had given us the lead only for Orient to equalise with 15 minutes or so remaining. Brown’s late winner made the once-inevitable relegation now seem more unlikely than likely, and wins in our next two games against Plymouth – courtesy of yet another Brabin goal – and at Southend on a Friday night thanks to a volley by Dai D’Auria set up the next game – at home to bottom-of-the-table Scarborough – nicely.

Many City fans talk of the Scarborough game as if it were crucial to our survival that season. It wasn’t really. The hard work done in the three games before had given us a comfortable cushion over Scarborough and Hartlepool, but a win against our North Yorkshire rivals would all but seal our survival. The Hull public – aware of this fact – turned out in force on that sunny April afternoon. The official attendance figure that day was 13,949. I’ve never met a City fan who was there who believes this figure. But Boothferry Park was crammed full for its first five-figure attendance in five years to witness a nervy game in which Brabin scored for City, only for Scarborough to equalise in the second half as City sat back on their lead. While the draw was disappointing, the point was of more use to us than it was the Seasiders.

A draw at Cardiff was followed by a win at home to Exeter as the occasionally maligned Colin Alcide silenced some of his doubters with goals in each game. A couple of 0-0 draws sandwiched an entertaining if disappointing 3-2 home defeat to Scunthorpe, as we struggled towards the finishing line. We needed to avoid defeat at home to Torquay, sweaty Neville Southall and all, in the penultimate game of the season to make safety mathematically certain, and again, nearly 10,000 packed into Boothferry Park to see the Great Escape completed (except no one would ruin it by foolishly speaking English – do the football fans who talk so much of ‘Great Escapes’ actually realise that the escape they are basing this reference on actually failed?). David Brown beat Southall in a one-on-one to trigger celebrations all around Boothferry Park as the theme to the film was sung endlessly. What had once seemed impossible had been achieved with a game to spare, and we could look on and smile as Jimmy Glass condemned Scarborough to relegation and, ultimately, extinction.

Scarborough’s eventual extinction is a poignant reminder of the importance of our Great Escape. Had we kept hold of Hateley for even a little while longer, had we not been lucky enough to have Warren Joyce among our playing staff, had we not been able to sign the likes of Whittle and Brabin, who knows what might have happened? We might have bounced straight back up. But we might – with Buchanan and Hinchliffe running the club into the ground – have never come back from such a blow. We might, right now, be supporting a non-league FC City of Hull at Dene Park while Hull Dons’ league matches are being ignored at a pared-down version of the KC. But we’re not. We’re watching Championship football, and we’ve seen City play in the Premiership. And regardless of what would have become of Hull City had we succumbed to relegation that season, I think it’s fair to say that it’s unlikely that any of the amazing things that have happened to us over the past decade would have occurred were it not for the wondrous way we turned things around in 1999.

It is for this reason that we should never let the bright lights and razzmatazz of our current status cause us to forget the debt we owe Andy Oakes, David D’Auria, David Brown, Mike Edwards, Mark Greaves, Gerry Harrison, Steve Swales, Jon Whitney and Gareth Williams. That goes tenfold for the spine around which our survival was constructed – Gary Brabin and Justin Whittle. Add to that Tom Belton – who was to be ousted from the boardroom in the summer and replaced by the despicable Nick Buchanan. But chief among the heroes of that dizzying four months is Warren Joyce. He was never to manage us for a full season, but must go down as the most important manager in the club’s history. The steps we took under his stewardship were not just crucial to the club’s survival, they were the first on the road to Wembley, Old Trafford, the Emirates and Anfield.

BEST STAND DUST SHOWERS Fan Culture

Best: a superlative of ‘good’, meaning of the most excellent or desirable kind – though the word is often loosely used to describe something that’s less shit than whatever is surrounding it. Hence, Mel C was the ‘best’ singer in the Spice Girls, Benidorm is the ‘best’ ITV sitcom of the past 25 years, Carlsberg is probably the ‘best’ lager in the world, and Boothferry Park’s ‘Best Stand’ was fractionally less shit than the South Stand, North Stand or Kempton.

The Best Stand had very little going for it, other than the fact that it wasn’t one of the three other stands. Yes it housed The Well, and it was where the dignitaries and sponsors sat, but it was still shit. In the final 30 years or so of its existence, when it had basically been left to rot, it had the added benefit of showering City fans with dust, rubble and bits of masonry whenever a clearance from a City player (or a pin-point pass from Steve Terry) hit any part of the stand’s upper areas. If the ball happened to hit the part of the stand’s roofing above the players’ wives, it was often the highlight of a Saturday afternoon watching these ladies, done up to the nines (well, more like threes for the most part), having to pick bits of concrete out of their Mark Hill hair-dos. The KC has yet to show any signs of fraying, but should the day come it can only be hoped that it does so in as comical a fashion as its predecessor.

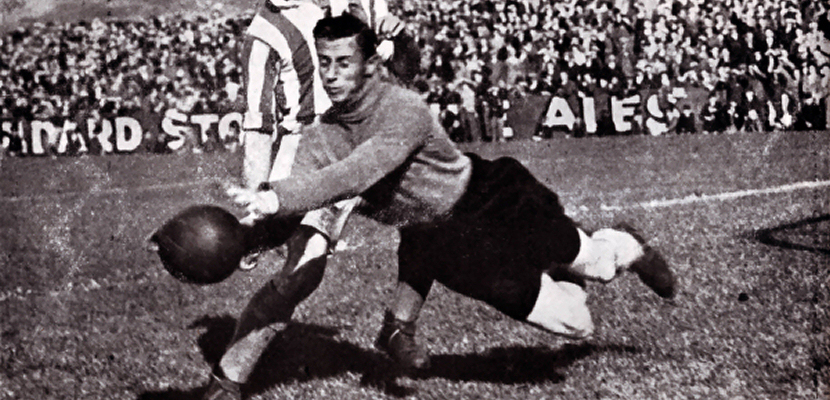

BILLY BLY Dramatis Personae

Hull City’s history might be a bit underwhelming, but our history of goalkeepers most certainly isn’t. From Eddie Roughley, reputed to have been outstanding in Hull City’s first serious stab at promotion to Division One, to the underappreciated Boaz Myhill more often than not standing as firm as could be expected behind such a porous Premiership defence, the list of Hull City greats is heavily weighted in favour of custodians of the leather.

Boaz would rightly have his supporters in an all-time City XI, as might George Maddison, Maurice Swan, Ian McKechnie, Jeff Wealands, Alan Fettis and maybe even Roy Carroll. In all likelihood, however, the green jersey would go to one of two men: Tony Norman or Billy Bly. In the event of a tie, the decision would have to go on who has the most pre-season trophies named after them.

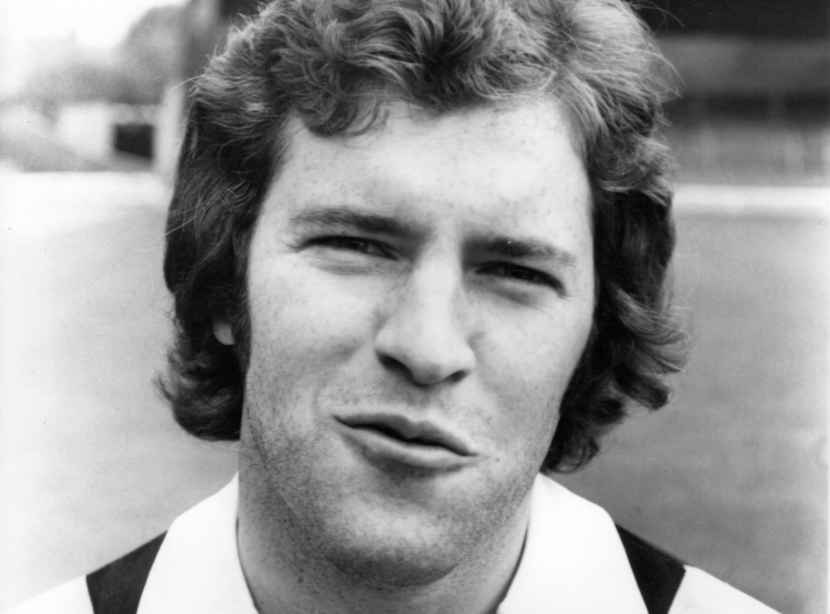

Bly was born in Newcastle in 1920 and came through his home town club’s youth system. It was while playing for Walker Celtic that he caught the eye of Ernie Blackburn and joined City as an apprentice in August 1937. However, Bly had to wait until April 1939 to make his debut at Rotherham in a 2-0 win though he was to remain City’s first-choice keeper for the remainder of the season. The war seemingly ended Bly’s City career before it had begun. Though he was to turn out for the club in a few wartime games, there could have been no clues that this skinny keeper who had played only a handful of games before the commencement of hostilities in Europe was going to stamp his name all over the history of the Tigers.

It was a 0-0 draw at home to Lincoln City in August 1946 in which Billy Bly’s City career started in earnest. He was first choice for City that day, and was to remain so until March 1960. Indeed had it not have been for a series of unfortunate injuries (Bly was reputed to be ‘the most injured man in football’ at the time) and the war robbing him of six years of his career, one can only wonder just how many more appearances than the eventual 456 Bly would have racked up in his 22 years at Hull City.

Bly’s star was to rise quickly. In the hubbub that surrounded Raich Carter’s appointment and the club’s rise in the next couple of years from half-decent Division Three (North) team to being on the verge of promotion to the First Division, Bly was outstanding. Carter’s class may have been taking the plaudits on a national scale, but among the City faithful Bly’s popularity was second to none.

In the famous 1949 FA Cup run, Bly kept an impressive clean sheet at Stoke in a 2-0 win to set up the famous Sixth Round tie at home to Manchester United. The 55,019 fans at Boothferry Park that day saw Bly break his nose in the first-half, and bravely play on despite clearly being concussed. It was such devotion to the cause that means that ten-a-penny fanzine writers are still writing about him 50 years on and why fans at the time loved him so much.

Injuries then started to hit Bly. He missed much of the 1950/51 season with a variety of injuries (his bravery was to see him suffer 14 fractures in his career, as well as a glut of other injuries). His fitness also seemed to be affecting any possible football career outside of the confines of Boothferry Park too, with Bly having to withdraw from an England ‘B’ call up due to injury.

The rest of the 1950s seemed to continue with a pattern of: Bly plays, City look fine; Bly is injured, City look shaky. Indeed Bly was to never be ever-present for City in any season. The closest he came was in 1958/59 when he missed just one game. It was no coincidence that that season City were promoted from Division Three.

Despite his obvious frailties, Billy was 39 when he played his final game for Hull City in a 1-0 defeat at Bristol Rovers. His final season was, predictably, blighted by injury, and again, City fortunes floundered in tandem. Relegation at the end of the season also saw Bly announce his retirement, 21 years or so since he’d made his debut in a career that spanned four decades. Bly came out of retirement to play for Weymouth two years after his last game for Hull City, and helped his new team to a giant-killing run into the fourth round of the FA Cup, but as far as league football was concerned he remained a one-club man. After his football career ended, he ran a sweet shop near Boothferry Park and remained a City fan after his playing days had ended.

So there’s much more to Billy Bly than a mere trophy. The trophy – usually presented to the victors of the North Ferriby v Hull City pre-season match by his son, Roy – means that his name stays in the consciousness of Hull City fans, but in truth his achievements while at City deserve more recognition than that. The longevity of his City career, his bravery, his talent, his likeability and the achievements of the club while he was stood between the sticks make Bly a worthy recipient of the title ‘legend’, a title that shouldn’t diminish with time.

THE HINCHLIFFE CREST Keeping Up Appearances

Back in 1999, at the start of a period of self inflicted financial turmoil that saw the club evicted from Boothferry Park, players go without pay and the taxman issuing High Court winding-up orders over unpaid VAT, the board saw fit to pay a few grand for an unneeded rebranding exercise. At the behest of vice president Stephen Hinchliffe, (a man disqualified from being a company director by the DTI and later convicted of fraud and jailed for two years) his nepotistically-appointed son James Hinchliffe was tasked to design a new crest. It was an utter abomination.

At the top of a shield was a crudely illustrated Humber Bridge that had three giant coronets hovering ominously, Damocles sword like, over the span. Underneath, inside the escutcheon, was an owl with a goatee beard rendered in iron filings, or maybe it was a clipart crab with a circumcised penis for a nose, or maybe, just maybe, it was a tigers head. It was supposed to be, but it sure didn’t look like one.

Thankfully, that design, which first appeared in a programme in March 1999 and inspired indignant protest, never graced the players’ kit. A hastily redrawn version was used on the Avec strips for 1999-2000 and 2000-2001, and though it was a little bit better, it was awful nonetheless, retaining the nose that looked startlingly phallic.

Adam Pearson sought to erase any trace of the ‘Sheffield Stealers’ reign when he brought the club out of administration in 2001 and heroically commissioned a new primary logo that contained the old, beloved tigers head design that had adorned City shirts between 1978 and 1999. Every now and then, however, the Hinchliffe crest is unwittingly used by a lax page editor in the national press, and the Tiger Nation is forcibly reminded of the time our club’s logo was, depending on your perspective, a bearded owl or a cock-nosed crab.

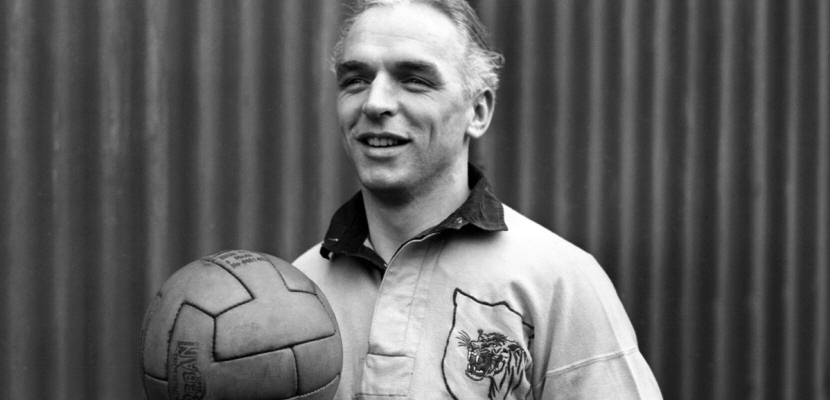

RAICH CARTER Dramatis Personae

Many Hullensians still have an understandable chip on their shoulder about the lack of publicity (and subsequent funding) regarding the pounding the city took from the Luftwaffe in the Second World War. If you don’t know the facts, then shame on you, but suffice to say that wartime Home Secretary Herbert Morrison considered Hull the worst affected city in the UK by such raids. Basically, post-war Hull was a mess and morale was at rock bottom.

Why am I going on about this? Because it helps put into context just how important Raich Carter was to the city and its football team.

Raich was a household name before he arrived in Hull. He’d won the FA Cup before the war with his home-town club Sunderland and then after it with Derby County. Still an England regular, In 1948, Raich was looking for a move into management. Assistant management offers flowed in, with two, Division Three North Hull City and Division Two Nottingham Forest, emerging as frontrunners. Mindful of the fact that City manager Major Frank Buckley was nearing retirement, and Forest boss Billy Walker was relatively young in management terms, Raich plumped for East Yorkshire, £6,000 was exchanged and a legend created.

On April 3rd 1948, Raich led out his new team-mates against York City in front of 33,000 at Boothferry Park. The game finished 1-1, and afterwards Raich immediately travelled up to Scotland to fulfil his duties as England reserve in a friendly at Hampden Park, so near yet so close to becoming our first England international. While Raich was away, his decision to join opt for City because of the potential for a quicker move into full management was proven to be a shrewd one. Major Buckley had fallen out with the City board, resigned, and Carter was offered the job one game into his City career, a move made official on April 23rd.

In the following summer, Carter signed former Sunderland FA Cup final team-mate Eddie Burbanks to add to an impressive-looking team that contained the likes of Billy Bly, Ken Harrison, Norman Moore and Jimmy Greenhalgh. City got off to a flyer that year, with Raich prompting from inside left and Boothferry Park regularly packing in 30,000-plus gates. The side remained unbeaten until October 16 when Darlington won 1-0 at Boothferry Park. Carter responded by signing Danish international and City legend-in-the-making Viggo Jensen. They weren’t to lose again until mid-February, in which time First Division Stoke had been knocked out of the FA Cup in the fifth round in a match at the Victoria Ground. City were the talk of the football world, with Carter’s profile remaining as high as it had been when he was playing in the top-flight. His presence was adding thousands to any game he played in.

Though clinching promotion was not quite a formality, the sixth-round tie at home to Manchester United in the FA Cup in 1949 captured the city’s, and nation’s, imagination in a way that that other sport could only dream of. Sadly, City lost 1-0 in front of our record home crowd. Unluckily too, by most accounts, with the ball reportedly going out of play just before Manchester United scored the game’s solitary goal.

Promotion to Division Two was sealed on April 30th after a 6-1 win at home to Stockport, with Carter netting twice. In the whole season, Raich had missed only three league games, scoring 14 times (level with Viggo Jensen and only behind centre-forward Moore’s 22). Football historian Peter Jeffs names Raich as the manager of the year in his ‘The Golden Age of Football’. Raich was the king of Hull. The city that had taken such a battering in the war – and had been largely been ignored by the national media – was given reasons to be both cheerful and optimistic. And it was Raich we had to thank.

So, Division Two beckoned. City had shown that we could match the best in the FA Cup the previous year, but could we sustain it over a full season? Did Raich’s 36-year-old legs have another full season in them? Would he be as effective at this level? Of course he would. City won 12 of the first 18 games of the season to challenge at the top of the table, with Raich scoring 13 times. Carter missed only three games all season, but was to only score three more times and a once-promising campaign faded as City won only one of the final 15 games, and finished what was generally viewed as a disappointing seventh

Raich started the 1950-51 season in incredible form, scoring in eight of City’s first nine games as the Tigers once again started a season among the division’s front-runners. However, an injury to Raich in November saw the good form tail off, and though it picked up again on Raich’s return, the gap to the top two couldn’t be breached and City had to settle for 10th. Yet again, there’d been plenty of cause for optimism, but how much longer could Carter go on for? And who could replace him on the pitch? His 35 appearances had brought with them 21 goals. Alf Ackerman and Syd Gerrie had been brought in to plug the goalscoring gap with some success, but replacing the irreplaceable? You might as well replace Michael Turner with Ibrahima Sonko.

The 1951/52 season started with the usual optimism. Though Raich had missed the team’s pre-season tour to Spain to care for his sick wife, he’d declared himself fit for another season. However, he was injured in the first game of the season – a goalless draw against Barnsley. Little did anyone know that it was to be his last game as City’s player manager. Carter handed in his resignation on September 5th, and it was unanimously accepted by the board on September 12th. Mystery shrouded Raich’s resignation. The board said nothing, and Raich’s vague explanation was that he’d quit because of “a disagreement on matters of a general nature in the conduct of the club’s affairs”.

The rumours that surrounded (and still surround) Raich’s exit just added to the highly unsatisfactory way in which such a great servant to the game and Hull City had left the club. His popularity remained undiminished with the people of Hull though, and the following season when City went on a 12-match winless run saw the board partially relent and allow Raich to return – as a player. The club’s fortunes improved with Raich dictating things, and the club staved off the relegation that once looked to be a certainty. The club even had time to beat First Division Manchester United 2-0 at Old Trafford in the third round of the FA Cup. Carter was man of the match. In the final game of the season – in what was to be Raich’s final game in the black and amber – Doncaster were beaten 1-0. The scorer? One Horatio Stratton Carter.

At the end of the season, Carter was given a civic testimonial by the Lord Mayor of Hull and the Carter family were showered with gifts from all kinds of companies and families connected with Hull. But the bitter truth was that Raich was going to move on, and when he did, it was surprisingly to Cork Athletic, but he was soon back in England, managing Leeds United and helping shape the early stages of the career of John Charles. After getting Leeds promoted to Division One, Raich resigned from Leeds because couldn’t recover from the board selling John Charles to Juventus. Managerial posts at Mansfield and Middlesbrough followed, but Raich’s managerial career, while impressive in places, was never to hit the heights of his playing days. After his sacking by Middlesbrough, Raich moved back to Willerby and made ends meet by starting his own football magazine, reporting on matches for the Daily Mirror, sitting on the pools panel and opening a newsagents close to where the KC is now situated. He remained a regular at Boothferry Park with his son, Raich Jr, but sadly only as a commendably passionate supporter.

Raich’s final ‘appearance’ at Boothferry Park came at half time in an otherwise forgettable 0-0 draw against Sunderland in October 1988. He and fellow Sunderland FA Cup final hero Bob Gurney dribbled a ball up and down the pitch as the crowd – to a man – stood to applaud them. The affection for Raich from all supporters was clear for anyone to see, several decades after he’d had any involvement with either club.

Raich died on October 9th, 1994 in Hull. At the time largely regarded as the club’s greatest ever player, the city mourned one of its finest adopted sons. At the request of then chairman Martin Fish, the funeral cortege stopped outside Boothferry Park to be met by a guard of honour formed by the playing and management staff and some 400 fans. His funeral ceremony was littered with football greats mourning a player who could stand shoulder to shoulder with any of them.

So where does Raich stand in what we can now hopefully call with some justification the ‘pantheon’ of City greats? Comparing players from different eras is in many ways futile. Who was the best Hull City player out of Carter, Waggy, Chillo, Whittle, Windass and Turner? Well only one of them thrived in the top-flight with the club, but that shouldn’t necessarily end the argument. Raich’s stats – 136 games, 57 goals – don’t necessarily tell the full story either, the story of the hope he gave a bomb-battered city and its underperforming football club, the flashes of skill that could change a game, the cheeky penalties where he would pass the ball to a team-mate instead of shooting, the fact that one of the country’s finest players was gracing the black and amber.

It’s hard to appreciate the present. Mention that Waggy and Chillo have been surpassed by Deano and Ash and you’ll generally get some Hull City fan over the age of 50 giving you a lecture on how two centre-forwards who for the most part couldn’t take City much higher than the middle of English football’s second tier were way better than anyone who played for us and against us between 2008 and 2010, despite plenty of evidence to the contrary. There is generally a third name added to the list of they who will never be bettered. Horatio Stratton Carter. That’s because it would seem he was every bit as good as misty-eyed nostalgics would tell you.

CALEB FOLAN JOINS FOR A MILLION Talking Points

Finally, we paid a million pounds for a player. And frankly, it was the first time our finances could really justify it. Adam Pearson’s support for Peter Taylor in the market was unflinching, but never could either chairman or manager have been able, even after elevation to the Championship, to apply reason to shelling out seven-figures on one player, especially as Taylor preferred to recruit from below. So, long after Taylor and Pearson had gone, it was Phil Brown who selected the player, using Paul Duffen’s resources, who would create City spending history. Caleb Folan had been deeply lacking in distinction during a brief loan spell years earlier during his kindergarten days with Leeds, but on August 31st, as the window was being pulled to, Brown offered a cheque to Wigan Athletic, whom City had dumped out of the Carling Cup, complete with Folan, days earlier, and they accepted.

Folan’s first act was to have his skull smashed by a wayward Blackpool forehead on his debut, but once he returned he proved an agile, able and awkward character who diminished initial doubts about his finishing (first goal wasn’t until December) by scoring crucially at Stoke, West Brom and in the play-offs against Watford, along with some invaluable strikes as a sub when Fraizer Campbell and Dean Windass were on form as the starting pair. He subsequently scored the goal that earned our first ever Premier League win, although injuries and an obvious inability to step up a level (or run around, or stay onside, or control a ball) made him peripheral and frustrating thereafter as relegation was fought against, and though he started the first four games of the second Premier League season, it was obvious that he wasn’t cut out for the job on any level except for actual effort, and was soon packed off on loan to Middlesbrough via a few disparaging words in Brown’s direction. Despite this, and irrespective of where he or the Tigers end up in the future, his contribution to promotion made the historic investment in his services prove more than shrewd.

HAROLD NEEDLER Dramatis Personae

As chairmen and owners go, Hull City know what it’s like to see both compassion and spite rule the roost in the boardroom. So many of the recent besuited figureheads have either emerged as icons worthy of immortalisation or villains worthy of incineration. Harold Needler’s commitment to the Tigers was long, unflinching, loyal and active to the very end – literally so, given that he was in control of the club until the day he died.

Needler bought the club when it was dead, gave it the new home that the previous regime had only seen half completed prior to the war dissolving any short term hope of a future, sorted out the identity as far as team colours were concerned (despite an initial period in an unattractive blue kit while awaiting the materials ordered) and appointed Major Frank Buckley as manager after initially using him as a go-between in a futile attempt to attract Stan Cullis from Wolves.

The 30 years that followed were sometimes eventful and regularly interesting. Needler’s natural character cut that of a benevolent and forward-thinking chairman, the type who would make the great Raich Carter the first player-manager of the type commonplace today and put his faith and confidence into the people who knew their job, offering Cliff Britton a ten-year contract to develop the club to the extent that it would be ready for the top flight of English football. He transferred £200,000 of his profits from sale of his construction company into the club in 1963 that funded a redevelopment of Boothferry Park and allowed Britton to purchase good players, most notably Ken Wagstaff. The ultimate ambition to reach the top tier didn’t quite happen, although the Tigers came mightily close in 1971 under youthful player-manager Terry Neill, one of many individuals associated with the Needler area that ferociously promote the man’s legacy to this day.

Needler’s sudden death in the summer of 1975 heralded a decline in the club’s fortunes, with his unsympathetic, undynamic son Christopher taking over for two years and maintaining a notorious family stranglehold on the club for many dark years afterwards. It is testament to the impact and stature of Harold Needler that he is still referred to reverentially by those who worked with him and supported the club during his tenure, even though the surname dually represents, thanks to his son, periods of disappointment, greed and profligacy.

HULL CITY RAILWAY PLAQUE Keeping Up Appearances

Acquired from LNER B17 class steam locomotive 2860 (later BR 61660), built in Darlington in 1936 and one of a group of locomotives named after football clubs, the elegant black and amber plaque, one of two that adorned the sides of the aforementioned train, enjoyed iconic status above the Boothferry Park tunnel for decades until the dastardly Martin Fish sold it to a collector and replaced it with a tatty plastic replica.

In the grand scheme of things it didn’t seem the most savage action of the Fish era, but it was witless and, thanks to no official club announcement until they were found out, desperately underhand. More than ten years on, and ever aware of a chance to show his caring, sharing side, Paul Duffen managed to find the purchaser and re-acquire it for the club, and it is now tacked resplendently to the very centre of the West Stand at the Circle.

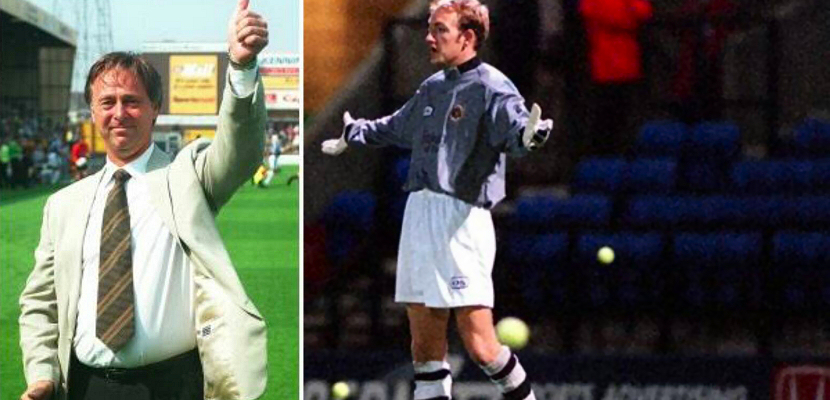

DON ROBINSON Dramatis Personae

Hull City had spent the later years of the 1970s and the early parts of the 1980s seemingly on a path to either non-league football or non-existence. The Waggy and Chillo golden years were now a distant memory and a couple of relegations had seen the club in the bottom division for the first time, with the receivers called in and no one within the city interested in saving it. The local media – when it bothered with football instead of rugby league – would generally focus on stories of funeral marches to the ground, collections to pay the players’ wages, how low attendances were…

An hour or so up the east coast, Scarborough were making waves as the most forward-thinking and successful non-league football club in the country, underpinned by consecutive FA Trophy successes. The owner of Scarborough was an eccentric businessman, a one-time professional wrestler who’d turned up at Craven Park one day claiming to be one of the finest prop forwards in rugby league. He wasn’t. He was an astute businessman, however, with a natural flair for promoting whatever it was that piqued his interest at the time. More often than not, it was himself. From 1982 to 1989, it was Hull City. The man’s name was Don Robinson.

When, in May 1982, the SOS call to Don came from Christopher Needler, with City in deep financial trouble, he couldn’t get to Hull fast enough. A £250,000 cheque was signed and Don was our majority shareholder, while Boothferry Park was purchased by a foundation set up by the Needler family. Don Robinson was our new chairman. He brought Colin Appleton with him from Scarborough to become our new manager. Hull City were about to embark on a journey that was fun and thrilling. The moon was the limit.

First up, red – Scarborough red, though Don claimed it represented the blood City players were going to shed for the club’s cause – was added to our kit. We looked uncannily like Watford. It was one of many changes that were happening at the club. Don would stand on Boothferry Halt selling raffle tickets before games. Robinson bought his own season ticket, “like the other fans”. Crucially, things picked up on the pitch too. Under Appleton, and with the likes of Garreth Roberts, Brian Marwood, Tony Norman, Pete Skipper, Billy Askew and Billy Whitehurst flying, City were promoted in Robinson and Appleton’s first full season running things. Don handed out champagne to the crowd afterwards to anyone – children included – who wanted some.

We were doing things that Hull City just didn’t do. Tours of exotic places were introduced – Florida, the Caribbean – adding the, ahem, illustrious Arrow Air trophy to the club’s threadbare trophy cabinet. Return friendlies with touring American teams were organised. Don would come onto the pitch riding a white horse and wearing a cowboy hat. Emlyn Hughes – probably the most recognisable footballer in the county at the time thanks to his captain’s role on A Question of Sport – played a handful of games for the club and was to act as a director in later years. We were – Don told us – going to be the first club to play on the moon. You couldn’t really be sure that he hadn’t already bought a rocketship on the cheap in preparation.

After our promotion from Division 4 in 1983 the trick was very nearly repeated the season after, the Tigers falling one goal short of a promotion-sealing win on that fateful night at Burnley. The aftermath of the game saw Appleton resign, presenting Don with the first big test of his regime. The result? A masterstroke.

Hull City were an upwardly mobile club and the vacancy was enticing for young and old managers alike. It therefore came as something of a shock when Robinson appointed Brian Horton – a midfielder at Luton – as our player-manager. The result was a promotion the next season and, with the likes of Richard Jobson, Garry Parker and Frankie Bunn now added to the side, an excellent first season back in the second tier, with City finishing sixth in Division 2 the season before the play-offs were introduced.

Everything about the club felt positive, home crowds were regularly hitting the 8,000 mark and Don was in his element. However, the good times couldn’t last. A few murmurings of unrest among the fans had started. The sale of Billy Whitehurst to Newcastle hadn’t gone down well. A sponsorship deal which resulted in the club having ‘Twydale Turkeys’ emblazoned across the shirts was poorly received. On the pitch, City’s form became inconsistent too. Had Don taken us as far as he could? There was a feeling that that was the case, though our chairman remained a popular figure among the fans and players.

The 1987/88 season was to sow the seeds to Don’s demise. An excellent start couldn’t be built upon and when we lined up at home to Swindon in mid-April, City had gone more than three months without a victory. As Swindon stuck four past a demoralised City defence that night, the crowd made their feelings felt and a sizeable number were calling for Horton’s sacking. There were also a few renditions of “Robbie out” to go with it. Don panicked and sacked Horton in the aftermath of the defeat. The next day, the players asked him to reconsider. Horton was asked to come back but refused. Hull City needed a new manager.

Don Robinson’s choice was former Leeds winger Eddie Gray, who’d spent his short managerial career inspiring Rochdale to not very much. Eddie enjoyed a mixed first season, with the disappointment of a fourth-from-bottom finish balanced against an excellent FA Cup run which saw us lose 3-2 in the fifth round to one of the great Liverpool sides. Gray had done enough to suggest there was something to build upon, only to be sacked at the end of the season. How much had been decided in advance is impossible to say, but Robinson returned to his first manager at the club – Colin Appleton.

The 1989/90 season was to be the last that would start with Don Robinson as Hull City’s chairman. It started in controversial circumstances. Unable to find a shirt sponsor, Don decided to simply have the word ‘Humberside’ printed across City shirts, as a thank you to Humberside County Council for the help they had offered the club over the years. At this point, the hatred of the word ‘Humberside’ – combined with the very existence of the county – was approaching fever pitch among those within what they considered to be East Yorkshire. That the announcement was made on August 1st – Yorkshire Day – only added to the depth of rancour among a not-inconsiderable number of City fans.

The shirt sponsor was nothing compared to the disaster that was to unfold on the pitch, however. Colin Appleton had been managing Bridlington Town in the Northern Counties league and was totally out of his depth back in league football. After starting the season with a 16-game winless streak in the league, Appleton was sacked and Don went with him, resigning as chairman and handing over the reins to Richard Chetham. Don stayed on as a director for a short while but bowed out quietly not long after, cutting his ties with the club. His name would appear as a potential savior during some of the darker days of the 1990s when the club was seemingly on the brink of collapse, but Don’s time with Hull City – a time he described later in the local press as “the best years of my life” – was done.

For all of his eccentricities and penchant for self-promotion, Don never forgot what was important, and therefore retains a level of affection with older generations of Hull City fans to this day. In an interview with the Hull Daily Mail years after leaving the club, he gave the following quote: “The biggest thing in football and in Hull is the fans. It’s their club, always will be, no one else’s. I felt I was part of those fans and I wanted to win as much as any fan.” The chances of anyone running our club at the moment coming out with anything approaching such a sentiment are about as likely as us playing on the moon.

So thanks Don. It was successful. It was unpredictable. It was excruciating at times. But sandwiched in-between the two grimmest periods of Hull City’s history, it was a hell of a lot of fun.

JON PARKIN’S FALL FROM GRACE Talking Points

Few were thrilled, to say the least, when Peter Taylor decided that lumpy, slow and dubiously skilled striker Jon Parkin was the right man to helm City’s progress in the Championship, for real money and everything. The memories of City fans who saw him in useless mode for York and laughed at him at Macclesfield were long. But Parkin was immense upon arrival, twatting defenders with aplomb while scoring peachy goals and quickly earning a cult status not seen for a man in his position since Billy Whitehurst was putting the shits up centre halves a generation earlier.

His winner against Leeds United near the end of that campaign seemingly secured his legacy forever, only to ruin it with an appalling lack of self-respect in pre-season that saw him arrive with a good few stones added to his already porcine appearance. Taylor had gone and Phil Parkinson didn’t have a clue what to do about Parkin, as now only his dreadful attitude fitted his nickname of the Beast, and apart from two sharp goals on telly against Sheffield Wednesday (reserving it for the cameras, eh?) he became an embarrassment, a target of fierce criticism not seen since John Moore. So from Whitehurst to Moore in the space of six months.

He fucked off to Stoke on loan as Phil Brown reached the end of his tether but had to come back in an injury crisis, during which time he proved he cared not a jot – including in a crucial game against his new bessies at Stoke, as City equalised in injury time but Parkin was the sole participant not to partake in the wild celebrations. Stoke bought him that summer and quickly they too realised what a fat, lazy waste of space he was, forwarding him to Preston within another year. An astonishing lurch from villain, to icon, to villain in such a short period.

HEDNESFORD CUP DEFEAT Depths of despair

The 1990s was a long procession of debasement and debilitation for those of a Tiger persuasion. Humiliations jostle with one another for supremacy in our scarred memories, with no clear winner, no definitive top ten possible, just an unending slurry of dismay. However, while we may never be able to select for certain our lowest point, few have a more vigorous claim than an afternoon of shame that’ll be forever known simply as “Hednesford”.

They were our opponents in the First Round of the FA Cup in 1997/98, a match played one chilly November day, a rancid affair replete with squalid cheating, loathsome officiating and a City side more mind-meltingly hopeless than anyone new to the support nowadays could believe ever turned out in amber and black. Those who do remember need only consider that Gage and Rioch were our full-backs that day, or wing-backs, as manager Mark Hateley attempted to mould them. Match of the Day were there too, featuring the Tigers on that evening’s show and fervently hoping for a “giant-killing”. They got one.

City started poorly, as was their wont. Hednesford now ply their trade in the Southern League, but at the time were a progressive Conference team, only a handful of places below the Tigers in the football pyramid. They probably had the better of the first half as a cold, sullen Boothferry Park crowd of 6,091 sighed with displeasure. Mick Norbury, veteran striker of virtually every crap northern team in existence, scored with a penalty shortly before half-time, comically awarded by Mr D Laws, a name not easily forgotten – for he turned in one of the worst refereeing displays ever witnessed.

The Pitmen led at the break, and City’s attempts to rescue the game in the second half were pitifully inept. Memories include Gregor Rioch (described as ‘barrel chested’ by Mark Lawrenson on MOTD) shooting from about fifty yards, as he did almost every game, Hateley bringing on the attacking duo of Ellington and Fewings (seriously) in bid to level matters, and Rioch tumbling in the area and Mr Laws waving it away before being almost jubilant as Hednesford scored again in injury time. The 1,000 Hednesford fans celebrated their cup final victory, their cretinous fat oaf of a manager pranced on our pitch, and we slunk away into the night in utter disgrace, wondering if we’d ever see the sun again.

SUPERMARKETS BEHIND THE NORTH STAND That’s SO Hull City

As the 1970s drew to a close and a swathe was cut through the North’s economy by a wicked woman from Grantham, Hull City AFC described a similar arc of decline. By 1982 the club had descended to the fourth division for the first time in its history and the disinterested Chris Needler had assumed the chairman’s post, only to plunge the club into receivership within six months of his second tenure. Struggling to stay afloat, the Tigers came perilously close to extinction.

In 1979 City’s directors had announced a scheme to develop Boothferry Park, with the Boothferry Road car park being given over to a complex of leisure facilities, a supermarket, club offices and a multi-storey car park. The proposal took three years to develop and was progressively scaled back to cut costs.

In February 1982 receivership and redevelopment plans crashed into each other. And so it came to pass that the fine North Stand structure with its imposing clock, was demolished and replaced by a functional supermarket shed that was occupied by Yorkshire grocery chain Grandways. The rear of the supermarket, which flanked the Boothferry Park pitch behind one goal, accommodated a shallow area of uncovered terracing that became an unsatisfactory home to many an away following for the next 20 years. It also housed an electronic scoreboard that would seem ludicrously basic now, but was considered to be a sign of the space age coming to Kingston upon Hull at the time. It clapped; it issued yellow cards; it responded when wayward shots narrowly missed it; it told the time. I was to all intents and purposes a miracle in electronic form.

Once a stadium that proudly boasted to being the only one with a dedicated British Railways station, now Boothferry Park was the only ground in English league football with a fruit and veg aisle behind one goal. The store closed early on matchdays so the spectacle of middle aged shoppers in headscarves mingling in the car park with the Fred Perry wearing hoolies of Middlesbrough and Derby never came to pass, but the embarrassment endured and Boothferry Park was denied much of its original cavernous atmosphere.

The decline of Boothferry Park, its name picked out in red backlit letters across the roofline of the store, was characterised most savagely by the failure of the club to replace busted light bulbs in the 1990s, which resulted in the stadium being announced to night-time passers-by as “—–FER– -ARK”.

Grandways begat Jacksons in the early 1990s and after a few years in this guise the store became a Kwik Save budget food seller. The store ceased trading in 2007 when Kwik Save went bust and was subsequently demolished along with the rest of Boothferry Park to make way for a housing development.

CHAMPIONSHIP SURVIVAL WHILE LEEDS ARE RELEGATED Talking points

So it’s us or Leeds to go down, and we have to go to Cardiff whereas Leeds, a point adrift of us, are at home to a middling Ipswich. One game remains after this so relegation may yet not be decided there and then, but if City could manage a win at Ninian Park, that’d be very handy, thank you. Few actually believed it would happen in tandem with Leeds conceding a hilarious late equaliser to Ipswich, prior to their lamebrained fans trying to get the match abandoned by invading the pitch, mind.

Dean Windass, three months into a glorious Indian summer with the club he adores, scored City’s only goal shortly after half time, and in front of a boisterous and euphoric travelling Tiger Nation. Every outfield player jumped on the 38 year old striker’s back, all part of the cause, though Leeds were winning too. But then Alan Lee, Ipswich’s effective lummox of a striker, completed the fairytale at Elland Road, and City were three points clear with a goal difference of considerable superiority. Leeds accepted their relegation before the maths confirmed it a week later, even taking a ten point deduction for administration and finishing bottom of the table.

We’ve had moments to celebrate our own achievements, but this one remains unique for the feeling of inflicting deserved damage on hated rivals which prompted, as a nice bonus, messages of congratulation from all other football fans. Hell, even the Cardiff fans more renowned for offering us steel toecaps and People’s Elbows were cheering for us by the end. And the following year we won the play-offs at Wembley to get to the Premier League, prior to Leeds losing theirs to Doncaster and staying in League One. Perfection.

TENNIS BALL PROTEST AT BOLTON Fan Culture

City fans were already miffed that tennis tosser David Lloyd had merged many functions of both the Tigers and egg-chasers Hull Sharks (as Hull FC were then known) such as the feebly named ‘Tiger-Sharks Inc.’ club shops, and were deeply suspicious that what little money Hull City had was being diverted to fund the rugby league clubs ambitions. The petulant fool had several times threatened to close both clubs down if the people of Hull (who he branded ‘crap’ in one interview) didn’t back his plans, and when he announced that City would leave Boothferry Park and become tenants at the dilapidated Boulevard ground, Tiger Nationals were enraged.

A beer fuelled meeting of the TOSS and Amber Nectar fanzines determined that protest needed to be made, and the forthcoming League Cup tie at Bolton seemed the perfect time. It was agreed that in order to truly grab the attention of the media, and in turn the sporting public, we needed to delay or disrupt the game somehow. A pitch invasion was deemed unacceptable as the publicity would be wholly negative, so a Nectarine suggested throwing tennis balls on the pitch, it made sense; it was non-violent, highly visible and amusingly ironic as former tennis pro Lloyd was the current Davis Cup captain.

A few hundred tennis balls were purchased and randomly distributed to willing supporters on the coaches bound for the Reebok Stadium. Just before kick off, they were hurled onto the turf, a few at first, then en-masse creating a vivid shower of luminous orbs to the bemusement of the players, officials and watching media. Radio Humberside’s Gwilym Lloyd, despite having been tipped off about the protest, curiously stated on air that it was apples being thrown at Steve Wilson, musing that maybe it was a twist on the old ‘oranges for Ian McKechnie’ ritual of yore. Nonetheless the media lapped it up, and each subsequent report in the national press increased the estimate of tennis balls used, a few hundred had become ‘thousands’. The protest worked better than anyone could have anticipated, and a humiliated Lloyd soon announced he was putting the club up for sale. Game, set and match to City fans.

LEIGH JENKINSON IN THE RUMBELOWS SPRINT CHALLENGE That’s SO Hull City

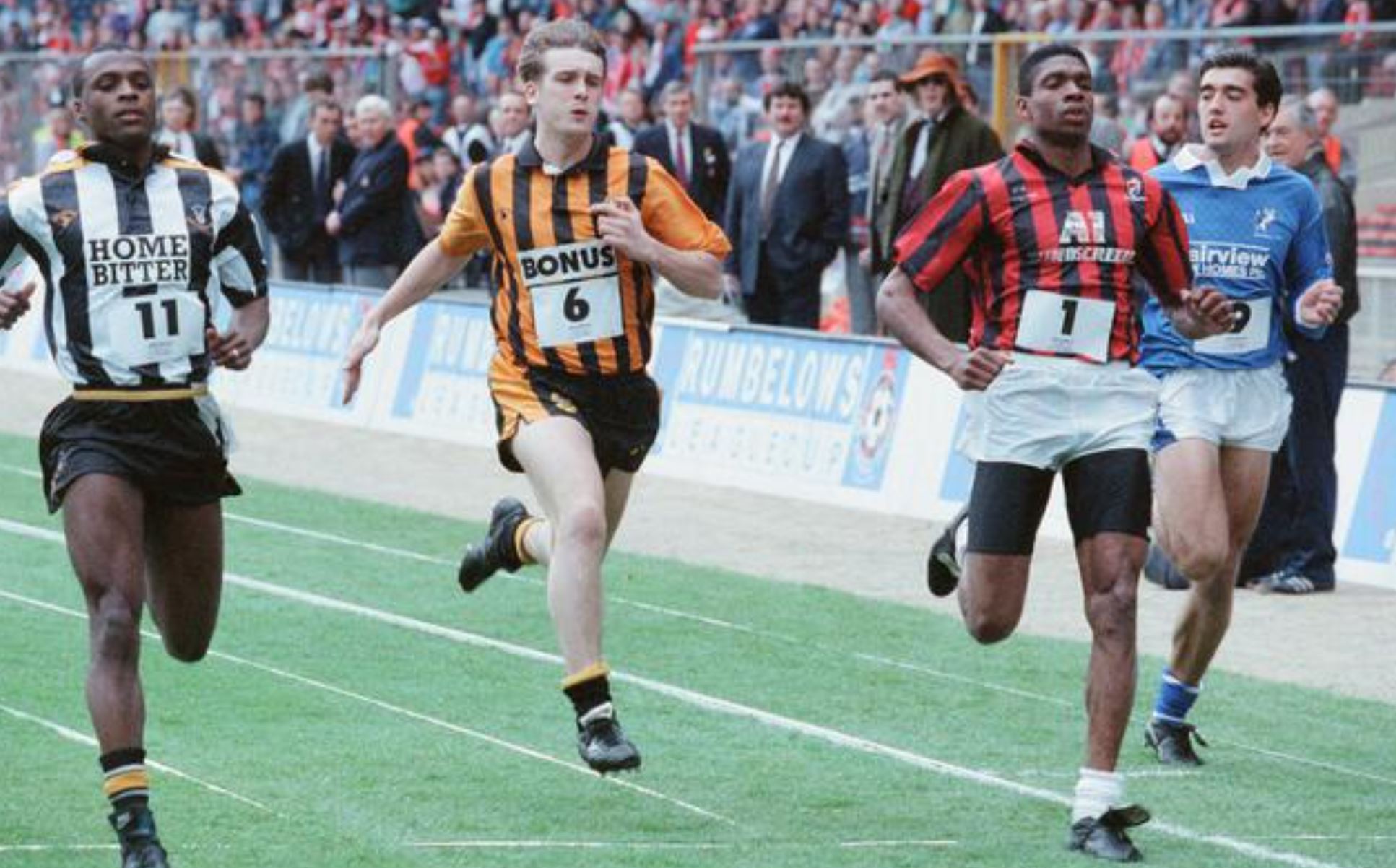

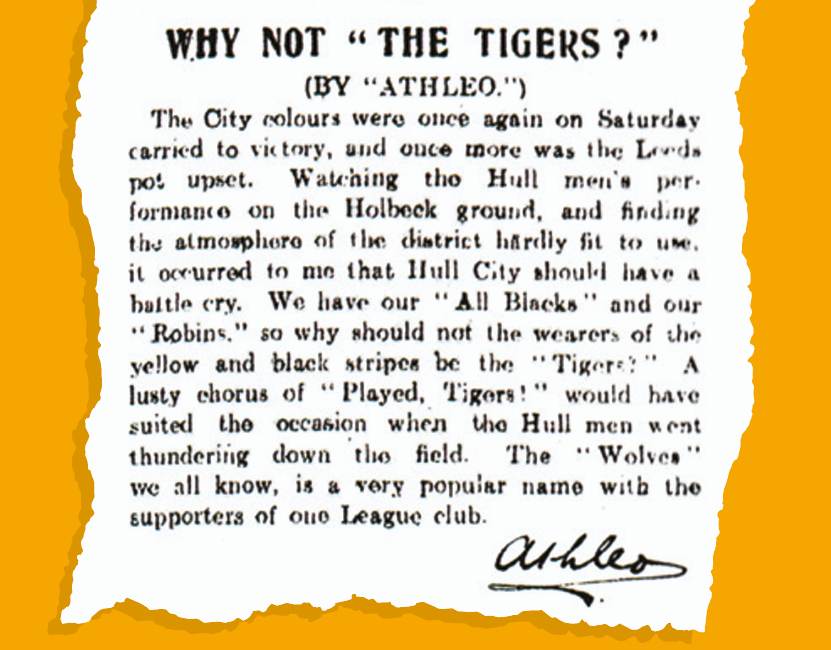

For 104 years we waited to play an actual match at Wembley, but at least it took only a mere 88 years before a Hull City kit was legitimately on show there. League Cup sponsors Rumbelows held an inter-club competition to find the fastest footballer in the 92, with each club (apart from those who thought it was a toss idea and declined) submitting their nippiest squad member, in football kit and boots.

Ultimately, a race at Wembley prior to the Rumbelows Cup final was the pinnacle. Regional heats were held, and although Jenks, the City winger renowned for being both fast and yet a carthorse (as well as slicing crosses into the South Stand with alarming regularity), was done by Huddersfield’s Iffy Onuora in his 100m semi at the Don Valley, he took him in the final and got to Wembley for the big occasion. There, with a sense of inevitability which summed up City’s fortunes in the entire 1990s (relegated twice, frequently humiliated), he came very, very last.

JEFF RADCLIFFE’S HAT Keeping up appearances

Few physiotherapists manage a quarter of a century at one club, and even fewer physiotherapists’ tam-o’-shanters manage to survive the same quarter century. It’s perhaps not the most staggering fact to suggest Jeff Radcliffe was unique because he wore a tam-o’-shanter, but it certainly made him recognisable.

Bought for him by his Scottish mother, he began wearing it after realising that sitting in a dugout watching a terrible game could be quite a cold experience, and the sight of this bobbled head nodding up and down as he ran across the pitch to spray Garreth Roberts’ knee (again) was often more thrilling than the football. One assumes that the hat was dunked in team baths, nicked, placed halfway up floodlights and probably shat in by Billy Whitehurst over its lifespan at Boothferry Park, but it was always there, on Radcliffe’s head, on matchdays.

Such was the impact of said millinery item that nobody recognised Radcliffe when he took to the field in his 1988 testimonial match; indeed only the sight of City and Spurs players applauding him on to the park gave his identity away. An example to any non-playing football employee of how headgear can look good and become part of your already likeable personality – Tony Pulis take note.

COLIN APPLETON Dramatis Personae

Grumbles of an old boys network and genuine concerns for the club’s future were clearly audible when the wispy-haired Appleton, a former chippie and captain of Leicester City, was appointed in the summer of 1982 by new chairman Don Robinson as the man to remove the Tigers from the abyss of the Fourth Division as quickly as possible. Relegation, within financial meltdown, had forced the club to its knees, but while Robinson’s rescue package was greeted with gratitude and open arms, his decision to bring his manager buddy from Scarborough in as well was less warmly received.

No-one need have worried. The two were a killer combination, but Robinson’s scheming, gimmickry and good-natured headline-grabbing often overshadowed the reflective Appleton’s sturdy work with his inherited squad, unable as he was to add many of his own purchases to it, though he did snap up freebie winger Billy Askew after a trial, a player who would be crucial to City’s progress for the rest of the decade. Appleton soon got into his stride, recognising the fearless gift in front of goal of teenage striker Andy Flounders and the creative might (and penalty-taking excellence) of the fast-developing Brian Marwood, all while garnering his predominant reputation as a manager who was obsessed with safe football and strong defence. City duly lost just six times, remained undefeated at Boothferry Park until the March (conceding just 14 goals there all season) and were promoted with two games to spare, eventually finishing as runners-up to Wimbledon. Hell, he even signed Emlyn Hughes for a bit.

Appleton again didn’t feel the need to change much for the return to Division Three and was vindicated with another season of effective percentage football that didn’t always please the eye but regularly turned up results, again thanks in no small measure to the mercurial Marwood, who put away another 16 goals from the flanks and the penalty spot. But the climate intervened in the January as City lost momentum and a whole month of games due to the weather and played an exhausting catch-up for the rest of the campaign, eventually needing a 3-0 win at Burnley in the final fixture to go up again via goal difference. Marwood scored twice but nobody could add the third, and the only cheers heard at Turf Moor on the final whistle were those of interloping Sheffield United fans, whose team had benefitted from City’s last-ditch failure.

Appleton quit before the journey back to Hull had been completed, to everyone’s utter horror, and went to Swansea, even not bothering to hang about for the remainder of the Associate Members Cup campaign. The recruitment of the excellent Brian Horton as his successor meant he soon wasn’t missed but his legacy was secure, even remaining so when Robinson brought him back for a wretched second go in 1989 (“How does feel to be back Colin?” “Er, I’m on cloud seven…”) which resulted in no wins from 16 games and, when Robinson then gave up the club, instant dismissal from new chairman Richard Chetham.

His willingness to let Robinson do the talking, plus the brevity of his stay and the manner of his departure, unduly devalue Appleton’s spell at the helm, but Appleton’s record during those two campaigns make him City’s best ever gaffer on pure stats. That he is also the worst, courtesy of his apparent inability to beat a carpet, let alone an opposing football team, upon his return in 1989, somehow adds to his legend and charm, and is easily forgiven when held alongside those astonishing achievements from 1982 to 1984. Those two seasons of salvage and hope make this softly-spoken, modest man just as important to his era of management as the likes of Warren Joyce and Phil Brown would later be in other turbulent periods for the club.

Now pushing 80 and still living in Scarborough, Appleton regularly rummages through a huge cardboard box of keepsakes – programmes, contracts, newspaper cuttings, photographs – in his attic that remind him of his time at Boothferry Park. His memories of being Hull City manager are very fond, and he can be assured that the supporters who watched his sides play feel the same.

CITY BLOW CHANCE OF TOP FLIGHT PROMOTION, 1910 Depths of despair

Oldham Athletic. When they’re not stealing Jobbo for half his true worth, or poaching our best schoolboy players of the late 80s and early 90s, or gaining an unfair advantage on a plastic pitch, or persuading us to overpay for Andy Holt, then they are pipping us to promotion to the top-flight of English football 100 years ago. Bastards.

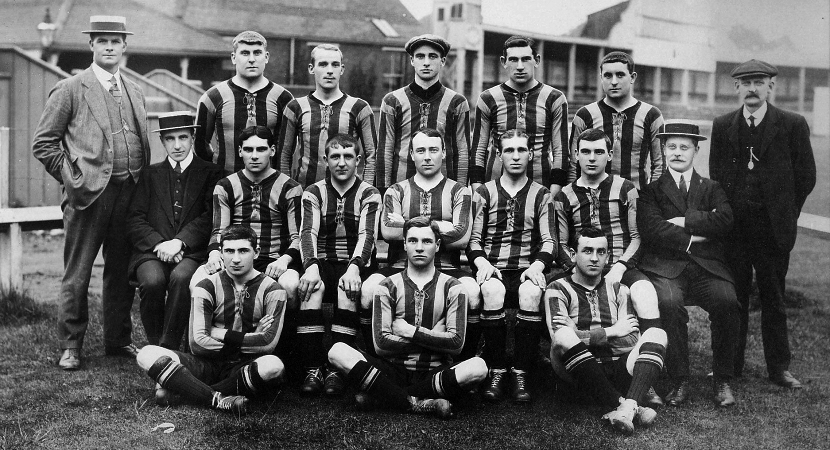

1910 was when we managed to mess up the best chance we’d had of promotion to what was then known as Division One, and were to get for another 98 years. City’s team back then doesn’t quite roll off the tongue like the great post-war teams but that’s more to do with the length of time that has passed than it is the quality of the players. You’ve all probably heard of EDG ‘Gordon’ Wright. Some of you may even believe that he was our first and only England international (he wasn’t; official FA records have him down as a Cambridge University player, unfortunately). But there was more to this team than the Hymers College schoolmaster. Manager Ambrose Langley seemed to want to field teams with as few surnames as possible, meaning the defence and midfield was based around the Browell brothers, George and Albert, while up front the goals were largely supplied and scored by ‘the three Smiths’, Joe (five goals), Jack (32 in 35 games) and Wallace (17). Davy and Dan Gordon were also crucial members of the squad. And in addition to Gordon Wright’s impeccable wing play, City’s forward line was usually completed by Arthur Temple – who contributed 16 goals that season – or occasionally the highly rated Alf Toward, who Langley deemed surplus to requirements and sold to Oldham for £350 mid-season.

City didn’t seem to miss Toward – who had contributed little that season anyway. Going into the final game of the season in second place, City needed to win at Oldham, who were two points behind but with a better goal average, which was how teams on level points were separated, or draw and hope that third-placed Derby didn’t win. As City went into the game unbeaten in 12 games, 11 of which were wins, top-flight football was City’s to lose. And lose it they did.

Derby did their bit, only managing to draw against West Brom, but City were blown away by Oldham. Missing the influential Jack McQuillan, City had no answer to the Latics attacking football. The home side went ahead on 18 minutes, and were two up on 25 minutes when – you guessed it – Alf Toward scored from what looked like an offside position. The third in the 80th minute compounded the agony. Oldham – who had spent much of the early part of the season propping up the Second Division – were promoted. City were left vowing to make amends the following season. And the season after, and the season after, and the season after…

And that was it. Of course we finished sixth in Division Two in 1986 – the year before the play-offs came into being –but until 2008 this was the nearest City had come to experiencing the upper chamber of the football league. It can only be speculated what might have happened had we won that day. Would we have gone on to greater things, build on the success and flirt with greatness in the way in which teams from similar-sized cities and towns with similar resources to City managed? Or would we have come straight back down and endured a very similar path to the one we were to tread anyway?

One thing we can be sure of, however, is that we wouldn’t have got to witness the too-good-to-be-described-in-words events of May 2008. Sure, promotion would have been incredible even if it hadn’t been our first time in the top flight, but knowing that we were prising a 104-year-old monkey off our back made the celebrations all the more elating and tear-inducing. So while our great-great grandfathers missed out on the opportunity to sup celebratory halves of milk stout down Canal Street, them being denied their bit of history made the bottles of over-priced piss that we got hammered on on the streets of Camden and Soho taste all the sweeter.

‘THE TIGERS ARE BACK’ RECORD Talking points

The football record has all but died a death, apart from every four years when some deluded ego is roped in by the FA to write something for the England team that they mistakenly believe will be a fraction as good as World in Motion. Or Vindaloo, for that matter.

The 70s and 80s were a different matter. Football records were all the rage. You couldn’t move for Nice One Cyrils, Back Homes, Anfield Raps and Ossie Ardiles’ knees going all trembly. Seeing the potential in this, a newly resurgent Hull City decided in 1981 that a seven-inch single was the best way to celebrate our ‘revival’.

We didn’t have a Chas and Dave among our fans, but we did have a soon-to-be award-winning film writer/director and a soon-to-be member of The Christians among our fans, and so schoolfriends Mark Herman and Henry Preistman were soon laying down some beats, or whatever it is that these people do.

The result is interesting. And if you think that ‘interesting’ is a euphemism for ‘a bit shit’, you’d be right. But shit in an endearing way. Lines such as “We used to roar a lot, along with 20,000 others” mixed seamlessly with crowd shouts of “Give ‘em some stick Dennis” in a deliciously low-key offering complete with a classy sounding 80s synth. Sadly, the top 40 didn’t quite beckon for this offering, but it remains the only Hull City record ever to be released. And in the general crimes against music committed by various football clubs or players, there has been much, much worse released.

JAMES CHESTER’S GOAL AT CARDIFF Heights of joy

City have had a share of “I was there” moments of late – three trips to Wembley, wins over Premier League opposition, European adventures – but these are obvious and many can lay claim to them. However, the more soulful type of “I was there” moment (and that’s why we’re here) lends itself to specific, idiosyncratic or just brilliant moments, rather than occasions, and if they were witnessed by only a smattering of people, all the better. They can be as ridiculous or as delightful as you see fit, and in the case of James Chester’s goal at Cardiff, it was absolutely a delight.

To many, it will set the benchmark for the great team goal, the type that doesn’t end with a thunderous volley or aerodynamic diving header but still epitomises how beautiful football can be. Chester, settled into the back four of the post-apocalyptic side fashioned by Nigel Pearson, was already evidently a striking example of defensive excellence and style, but his goal at Cardiff’s shiny new stadium in the spring of 2012 gave him extra prestige.

He intercepted a pass in his own half, left the ball to Josh King – and just kept running. King fed Robert Koren, the Slovene then reached the edge of the box before returning it to King who instantly flick-heeled it behind him to an unmarked, unnoticed Chester, and as everyone tried to work out how he got there, he steered it under the keeper and in.

It was a divine team goal, made to look easy from start to finish and sandwiched two further strikes to give City a 3-0 away win that was the most impressive performance of a season that nearly, under Nick Barmby, resulted in a play-off place.

City ran out of puff in the end – the same month saw eight more games squeezed in – but Chester’s name, a name that endured after Barmby and into the Steve Bruce era of promotion, Premier League returns, the FA Cup final and Europe, was made with fans that night.

ANDY PAYTON V. BRIGHTON Heights of joy

Memories are great things. Totally unreliable, of course, but great nonetheless. Thanks to the internet, Sky and the general profile of football, every last detail in any Football League game is now recorded from any number of angles. You don’t need to remember goals, you just need access to YouTube or Virgin Media.

Of course none of these things were available when Andy Payton inspired City to an enthralling 5-2 demolition of Brighton in December 1988. I haven’t seen Payton’s second goal that day since I witnessed it while freezing to death on the South Stand. My memory tells me that he picked the ball up on the edge of his own area and ran in zig-zags past eight Brighton players before scoring from an acute angle. He didn’t. I accept that.

If I strain my memory I know that the goal was still remarkable; that Payton picked up the ball in his own half, beat the two centre-backs in the centre circle, skipped past a full back and rounded the keeper from the afore mentioned acute angle. But YouTube or ESPN Classic are never going to prove me wrong or right. Payton – a player who really should be higher in the pantheon of Hull City greats than many seem to rank him – was to score many more goals for City, and a good few of them were spectacular, but he was never to get close to this incredible run, at a time when he was only really on the verge of cementing his place in City’s first team.

The soon-to-be-ignited Edwards and Whitehurst partnership was to delay his rise for a while, but this goal told us everything we needed to know about Payton: he was going to be a star.

THE WELL That’s SO Hull City